Currently, you would be forgiven for feeling a little bit demonised as a landlord, both personally and from a business perspective.

Landlords are regularly accused of preventing first-time buyers getting on the ladder, charging ‘extortionate’ rents, then putting through ‘sky rocketing’ rent increases and evicting tenants ‘at a whim’ with short-term, six-month contracts. This wave of criticism has now been topped with accusations of landlords ‘pocketing’ housing benefit – as if it’s an illegal act – and, most recently, of discriminating against tenants on benefits, alongside agents. (https://england.shelter.org.uk/media/press_releases/articles/no_dss_five_leading_letting_agents_risk_breaking_discrimination_law)

I find this criticism quite odd in itself and, in many cases, unfair. That’s because most landlords and letting agents provide a much-needed service and there is very little evidence in my view, let alone balance, in much of the criticism.

When it comes to the growth in demand for properties to rent, it’s often forgotten that much of this demand was driven by successive government policies. In the late ‘80s, the Conservatives wanted to get rid of social housing and encourage people towards renting privately – even if it did mean taxpayers’ money being spent in the private sector via housing benefit. What’s rarely mentioned is the investment that private landlords make to create a home for tenants in the first place, which saves the taxpayer the cost of buying land, building and maintaining a property. And there is no mention of the tax paid by the landlord to the government via stamp duty and a percentage of any property income they earn.

Labour’s plans, under Tony Blair and Gordon Brown, resulted in a huge rise in the number of students going to university, followed by a big increase in the number of migrant workers, which greatly increased the demand for rental properties.

Then the recession hit and lenders withdrew 5-10% deposits, along with the ability for most first-time buyers to get on the ladder. For several years, average property prices continued to fall so, in addition to all the would-be first-time buyers staying in the rental sector, many families who needed to move ended up letting their existing home and buying or renting a new one. So the recession boosted both rental supply and tenant demand.

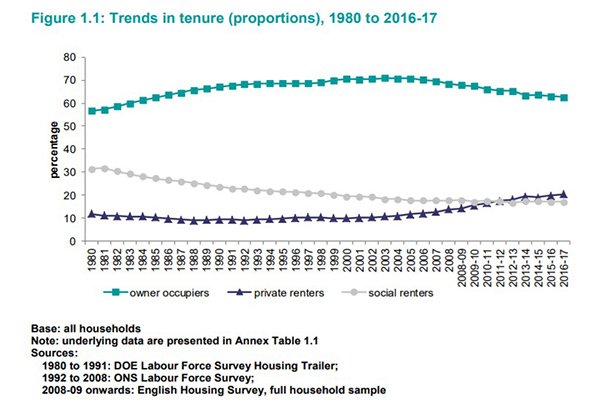

And it’s interesting when you look at the statistics from the English Housing Survey to see where new homes have come from. It’s often quoted that the Private Rented Sector (PRS) has doubled at the expense of home ownership, but the chart below shows that this simply isn’t true.

The PRS has clearly taken a huge amount of share from the social sector as well as the owner-occupied sector. However, bearing in mind that we lost around 50% of buyers for up to 5 years in some areas following the credit crunch, it’s not a huge surprise that the PRS has grown in comparison.

But making a statement about how people live purely by going on the percentage of people owning, renting and in social housing, can be misleading.

Looking at actual numbers shows a bit of a different story:-

| 2000 | 2016-17 | +/- | |

| Owner Occupiers | 14,339 | 14,444 | +1% |

| Private Renters | 2,029 | 4,692 | +131% |

| Social Renters | 3,953 | 3,947 | N/C |

| Total: | 20,320 | 23,083 | +13.6% |

Source: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistical-data-sets/tenure-trends-and-cross-tenure-analysis

What this data shows is that, despite the percentage fall in social housing, there are no fewer people renting socially today than back in 2000 and it’s a similar picture for those owning a home.

So, yes, the PRS has grown, but it’s not in physical numbers at the expense of any other tenure. What it also suggests is that the PRS must have created a huge number of additional homes for its own sector, as opposed to simply have ‘stolen’ them from other sectors as landlords are often accused.

Add to this the huge crackdown on affordability by the government’s new rules on lending, public sector pay caps – many way below property price inflation – and the private sector keeping wages low, and it’s no wonder renting has grown – often more affordable and more suitable for people in today’s “gig” economy.

In other words, the overall growth of the PRS isn’t the ‘fault’ of landlords or letting agents; it’s down to government policy and economic changes, none of which the PRS caused.

If landlords are providing a necessary service, why is there so much criticism?

Essentially, in my view, it appears to be politically motivated, rather than based on real facts and figures. There are more tenants than landlords, so they now form a higher percentage of likely voters than ever before. In addition, there is one valid reason for the increased focus, which is that there are more families in the sector than ever before – no surprise, considering the lack of social housing available and that many of these properties are taken by single parents.

Nevertheless, those that criticise the sector seem to only have two targets in mind: landlords and agents. What’s really interesting is that few organisations and/or politicians ever tackle or criticise those that fund and insure the private rented sector: mortgage lenders and landlord insurance providers.

For example, the recent attack on landlords and letting agents by both Shelter and the National Housing Federation never once mentioned the fact that many can’t rent to those on benefits even if they wanted to, because so many lenders and insurers exclude tenants on benefits. In my view, this is very odd. If there’s a clear problem and you really want to get things changed, why not go to the source of the issue?

And it’s the same for six-month rental agreements, which are often blamed on ‘greedy landlords’ and ‘fleecing agents’. However, the six-month agreement was driven by the lending community, who, on being asked to provide specialist buy to let mortgages, wanted a ‘fair’ time within which they could repossess the property if the tenant didn’t pay and the landlord subsequently defaulted on their mortgage.

Will things ever get better for landlords?

The short answer is ‘yes’. At the moment, there is a lot of poor information and biased analysis being used to try and drive both some much-needed changes and other changes that really won’t make any difference. But it makes great political and newsworthy rhetoric, and ensures this and previous governments aren’t blamed for housing problems, instead they can let landlords and letting agents take the blame.

But, as far as I’m concerned, this can only carry on for a little longer. According to research from our Belvoir Rental Survey, the onslaught against landlords from increased taxation and a constant stream of new rules and regulations is starting to bite. Belvoir agents are reporting that their landlords are starting to sell up (link to latest press release/report)

Currently, many of these sales will be reported as contributing to a ‘growth in evictions’ from the private rented sector and are being used to try and drive a change in the law to bring three-year minimum tenancies into force.

However, the reality is starting to hit. Hurt landlords and you hurt tenants, especially vulnerable ones. When you couple financial hardship caused by the widely-criticised introduction of Universal Credit and caps on local housing allowance, with landlords leaving the market and evicting tenants because they’re selling up, the result is that many tenants now have nowhere to go, as there simply isn’t enough social housing to support them.

This was covered in a report from Crisis, in partnership with Joseph Rowntree Foundation, which states: “All available evidence points to Local Housing Allowance reforms as a major driver of this association between loss of private tenancies and homelessness.” and that “89 per cent [of councils] reported difficulties in finding private rented accommodation.”

Source: https://www.crisis.org.uk/media/238701/homelessness_monitor_england_es_2018.pdf

In other words, the naïve and simplistic view of politicians that if you reduce the number of landlords, first-time buyers will be able to magically ‘buy’ a property, is at last being replaced. It’s now starting to be reported that a loss of landlords leads to a rise in evictions of tenants who then have nowhere else to live and that is resulting in a rise in homelessness.

It’s this latter, much-needed ‘change in hearts and minds’ that I believe will help critics start to see landlords – especially those that create new rental homes – as a solution to, rather than a cause of current housing problems.

As long as this is achieved, along with all letting agents in England having to be regulated (as is already the law in Scotland and Wales), private renting should soon be seen as a valuable tenure, offering a good service to it’s customers as opposed to one that has to be curbed.